“…much of what was said did not matter, and much of what mattered could not be said.” (P.172)

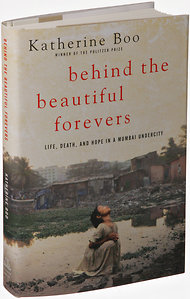

Behind the Beautiful Forevers, written by journalist Katherine Boo, is set in Annawadi, a slum in Mumbai, stretching along the Mumbai Airport and hidden from view by a concrete wall that separates the indulgent from the destitute, the opulent from the deprived. Home to 3,000 residents inhabiting half an acre, this story could have easily taken place in Karachi, Pakistan, Nairobi, Africa, Cape Town, South Africa, or Mexico City (the top five slums in the world according to the United Nations – A report, that actually identified, Neza-Chalco-Itza, one of Mexico City’s many barrios, as the largest slum in the world with roughly four million people inhabiting it (UN Habitat, 2013).

Behind the Beautiful Forevers, written by journalist Katherine Boo, is set in Annawadi, a slum in Mumbai, stretching along the Mumbai Airport and hidden from view by a concrete wall that separates the indulgent from the destitute, the opulent from the deprived. Home to 3,000 residents inhabiting half an acre, this story could have easily taken place in Karachi, Pakistan, Nairobi, Africa, Cape Town, South Africa, or Mexico City (the top five slums in the world according to the United Nations – A report, that actually identified, Neza-Chalco-Itza, one of Mexico City’s many barrios, as the largest slum in the world with roughly four million people inhabiting it (UN Habitat, 2013).

The book is described as a narrative non-fiction however I would not hesitate to label it as an ethnographic study told in a novel-like-style. In the author’s notes, we learn that Boo spent 3 years conducting fieldwork in the slum. With the aid of interpreters, the inhabitants were interviewed repeatedly and where possible, Boo herself would have long conversations with some of the youth, pressing them to share some of their thoughts and impressions, and looking to archival research to check and re-check her facts, as she documented a detailed in-depth description of everyday life for the Annawadians.

told in a novel-like-style. In the author’s notes, we learn that Boo spent 3 years conducting fieldwork in the slum. With the aid of interpreters, the inhabitants were interviewed repeatedly and where possible, Boo herself would have long conversations with some of the youth, pressing them to share some of their thoughts and impressions, and looking to archival research to check and re-check her facts, as she documented a detailed in-depth description of everyday life for the Annawadians.

In the telling of Behind the Beautiful Forevers, the author depicts an intimate and detailed portrait of a place and a people united by a desire to improve their lives and those of their loved ones at a time when the buzz words are global development, prosperity, and progress.

As I read the stories, I was reminded of something that always struck me whenever I crossed the streets in Asia and India. The Pedestrian Traffic Signal for WALK is a running man.  To reach the other side safely, you often had to run. Each time I crossed the street, I would be reminded how this running figure truly symbolizes life in these continents where so many are running in pursuit of progress and prosperous opportunities.

To reach the other side safely, you often had to run. Each time I crossed the street, I would be reminded how this running figure truly symbolizes life in these continents where so many are running in pursuit of progress and prosperous opportunities.

Through her narration, Boo invites the reader to witness the lives of such a people. Lives that consist of a delicate balance between thriving and surviving, doing and dodging. A people with limited access to resources – slum dwellers – for whom necessity has truly bred innovation, where the rich’s rag is literally a poor man’s treasure. Because an objective observation, devoid of an observer’s pre-existing attitudes, is simply impossible, we, as witnesses, interpret the Annawadi’s life using our own previous experiences, preconceptions, and ideas, in our attempt to understand and give meaning to the events we have witnessed.

Research that commands our attention to the likes of Annawadians, aiding us to discover hidden insights, about others and ourselves, is a research worth pursuing. As I reflect on Behind the Beautiful Forevers and ponder ethnography as a research method, I am aware of the potential of subjectivity in interpreting and in the observing of a culture. The lenses through which I see the world of the Annawadians are my lenses, giving me an understanding and an interpretation of the Annawadi culture that may differ from the Annawadis’ own perspectives and interpretations.

As I read the book, I was distraught at the poverty and corruption that the slum dwellers have to face daily but I also marveled at the resilience, ingenuity, and resourcefulness of the Annawadians and all self-reliant urban dwellers. They have once again shown me how humans can adapt to the direst of circumstances. The more I thought about the book, the more I thought about my own reflections and attitudes about global development. In that sense, this ethnographic study taught me more about my own understanding and worldviews than about the slum dwellers of Annawadi.